Learning the Three “R’s” Space Shuttle Style: Rollout, Rollback, Rollover (Part 1)

No one ever said photographing a shuttle launch would be easy, nor did I expect that it would be. I should know. After all, I have worked in the space industry for the last 16 years – some of those years with the shuttle program – and launch delays are part of the business. But until I got my feet on the ground, I never realized how frustrating it would be. Frustrating. Yes, that pretty much sums it up.

Rollout

While at Cape Canaveral on a work trip in mid-March 2011, I had the opportunity to see Space Shuttle Endeavour rollout from the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) to the launch pad for its final mission, STS-134. This is to be Endeavour’s last flight and the second to the last ever Space Shuttle flight. It was awe inspiring seeing powerful xenon spot beams lighting up the shuttle stack like a polished jewel against the darkness of night. This re-ignited my interest in the shuttle program. After seeing Endeavour rolling out, I thought why not make the experience whole and see the launch as well?

Endeavour after arriving at Pad 39A the next morning.

Crawler-Transporter near the entrance to Pad 39A after delivering Endeavour the previous evening.

Anticipation

I arranged for a NASA mission media credential, with the goal of taking remote photos of the launch within the launch “danger zone” near the vicinity of the launch pad. I had previously seen and photographed two shuttle launches: STS-97 from the NASA Causeway (10 miles away from the launch pad) and STS-102 from the Banana Creek / Saturn V Viewing Area (3 miles away from the launch pad) - but I had never photographed a shuttle launch remotely.

So how does one “remotely” take photos of a launch? As I found out, there is not a single answer. Most build and design their own triggers, while others buy custom triggers. I figured perhaps camera makers make an accessory to remotely trigger a camera based on sound or maybe light. Sadly, the answer is no. After many hours spent researching and performing google searches, I settled on a custom timer-trigger made by T-minus Productions, based upon a recommendation by launch photographer Ben Cooper. This is how my particular timer-trigger works: the timer is set based upon the start and end of a launch window. At the start of the launch window, the timer turns on the camera. At this point, the trigger starts to listen for the launch at a pre-determined decibel level and then fire off the camera when it hears the launch. The camera will continue to shoot as long as there is sound and will stop when there is no longer sound.

The next question was – where to set up my camera? There are many options and areas to choose from. Based upon lighting at launch time and the photogenic quality in this shot, I decided to set up my shot there. The trigger can drive two cameras. With that being the case, why not setup two cameras and take two views…one wide showing the entire scene and one tight zoomed in on the shuttle itself?

Many sleepless nights ensued. What kind of lens should I use? Should I rent, borrow, or buy a third camera and lens? What if an alligator walks by and tips over the camera? What about debris and fallout from the launch itself? What about rain? Do I feel comfortable leaving my cameras out in the wild near a swamp for potentially a few days straight? I am constantly reminded of the story behind this shot showing the dangers of remote launch photography.

On travel day, I had two carry-ons (both camera bags) and two rolling suitcases (one with clothes, the other filled with three tripods). I was not a pretty sight arriving in Orlando in 90 degree plus heat with humidity with four bags in tow walking to my rental car.

Launch Minus One Day: Hurry Up and Wait

STS-134 was scheduled for launch on Friday, April 29th. Remote camera setup was bright and early at 6 am on launch minus one day. There were no directions on what to do. Most, if not all of the photographers were old hands at this and I just played monkey see, monkey do. Everyone lined up their cameras and associated gear alongside waiting buses for bomb-sniffing dogs. As I later found out, buses take everyone to the same location first, and then rovers driving vans take photographers to other locations. This first location is known as the “mounds”, and it is a popular and favorite photo location for most. The mounds are located to the east of the launch pad immediately outside of the fence. Few mounds dot the area affording a clear view over the fence line. After arriving, photographers scramble to play “king of the mounds”.

A sophisticated Associated Press remote setup with antenna. Supposedly the setup transmits photos back to the Press Site immediately after launch, eliminating wait time for camera retrieval post launch.

View of Pad 39A from the mounds. The Rotating Service Structure (RSS) still has the orbiter itself covered up.

Rovers driving vans spend most of their morning shuttling higher priority photographers for wire services, such as AP or Reuters. Us amateurs wanting to setup from other locations had to wait patiently for a ride. While waiting, I ran into an old friend and fellow photographer Jean and his wife, Kanoko. Jean had photographed many shuttle launches and he was a sight for my sore eyes. Jean gave me pointers and explained how the whole thing works. It was a relief to finally gain some insight.After showing our escort the shot I wanted, I found out the spot I needed to go to is known as the “pipeline” (who knew all of these spots had names?). Another group was waiting to go to the “dike”, across the swamp on the eastside. Yet another spot, on the backside of the pad, known as the “tracks”, was easy to get to and the journey was easily accommodated. I waited four hours at the mounds in the hot Florida sun before a van was able to take me and three other photographers to the pipeline.

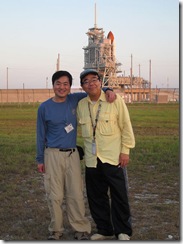

Jean and I at the mounds.

Taking cover in the bus shade while waiting for the rover.

My remote shoot gear.

It was show time. We ducked under the nitrogen pipeline (so that’s where the name came from!), and ventured behind bushes and made a quarter mile hike to the shore of a creek. It was dry and muddy closer to the pad, where I wanted my camera angle. I could have positioned further down to the water, but the angle to the launch pad would have been too oblique. I chose the better pad angle instead. I set up my tripods, stakes, and cameras. It was easy, just like how I practiced the setup in my backyard.Put the cameras on manual exposure and manual focus. Pre-focus. Tape the focus rings. Connect the timer-trigger, double check the launch windows on the timer, turn on the trigger, test fire the cameras. Click, click, click – both cameras go off – good. Turn off the trigger, making sure the timer is set on Auto. Double check – timer on Auto, right? Otherwise no photos! Bag the cameras.

The forecast called for rain that evening, so it was looking like my rigs would get their feet wet. I taped a garbage bag around my camera and tripod legs, leaving only the lens exposed. From my previous experience, I knew I could not leave the UV filter on my lens, otherwise I would get a nasty reflection from the bright rocket plume on the photo. Having a cup or hood around the lens is also not a good idea, because it would collect rainwater, creating a pool over the lens. So literally, the camera lens is totally exposed to the elements. After they are all set up, I walked away thinking: “did I forget anything?”

I had chosen white trash bags because they were the cheapest I could find. I later found out that white bags are better than black bags because animals and birds get into black bags looking for food (thinking they contain real trash).

View from my wide angle remote camera, about 0.6 miles from the pad. Lighting would have been better at launch time later in the day.

By noon, I was back at the Press Site where I met up my friend Sagar, a fellow photographer from my area. We explored the Press Site, toured the Lockheed Martin Orion display, and checked out the fancy Tweetup tent (all I got to say is those Tweeter winners received a nice prize from NASA – gift bags and fancy tours and all).

Sagar and I at the Press Site in front of the famous “big clock”. Pad 39A can be seen three miles away to the right of the clock.

NASA News Center at the Press Site.

Inside the News Center. When you are a noob like me, you sit on the floor!

Resident osprey nest in the parking lot at the Press Site.

Rollback

The next big event of the day was Rotating Service Structure (RSS) rollback. The RSS normally protects the orbiter (and obstructs the view of it) while the shuttle is on the pad. One day before launch, the RSS is rolled back, “unveiling” the orbiter and the entire shuttle stack. The rollback was scheduled to take place at 7 pm, right at dusk for some interesting lighting for photography. We joined the crowd lining up next to buses for a 5 pm scheduled departure. Then dark clouds moved in. We were told there was a phase 2 lightning warning. Everyone had to take cover either indoors, inside their cars, or on board buses. People tracked the passing storm on their iPhones and we could see the thunderstorm approaching from Titusville, to our west. Some hardcore photographers decided to ignore the lightning warning and setup their tripods outside to take lightning photos. The one thunderstorm cell became two. Two became three. All work on the launch pad stopped. We waited and waited. Us hearty souls waited in one of the buses and exchanged stories. We didn’t want to leave the Press Site for dinner in case the buses were ready to roll to the pad when the thunderstorms stopped. So we waited and waited. Dinner that night consisted of Snickers and trail mix from the vending machine with drinking fountain water. I would have had a Coke except the machine ran out. In the mean time, I was worried about my remote cameras. Did I tape the bags securely? What if the wind blew the bags off? Did the water level in the creek rise?

The VAB after one of the thunderstorms.

Finally, at 10:30 pm, everyone boarded buses and departed for the pad for RSS rollback, now scheduled for 11:30 pm, about 4 hours later than originally scheduled. There was a bit of jostling at the photo line across the crawlerway. If you didn’t get there fast enough, you wouldn’t get to set up your tripod in the front. Slowly, the RSS opened. Initially, it was barely perceptible, but it moved quickly after the RSS cleared the orbiter. I tried to take time elapsed shots, showing motion blur with the RSS moving. The entire rollback took around 30 minutes.By the time my bus arrived back at the Press Site, it was after 1 am (by now – launch day). I got back to my hotel in Cocoa Beach at 2 am. I had been at the Press Site that day from 6 am to 1 am.

Motion blur shot of the RSS rolling back.

Since my good wide-angle lens was being used on the remote camera, I had to use my not-so-great backup lens with my backup camera (a 20D). I was not happy with the result. Frustrated, I put my S95 point-and-shoot on the tripod…and it got better photos than the 20D. Go figure.

Launch Day That Never Was

When I arrived at the Press Site at Kennedy Space Center (KSC) a couple days prior, I noticed a queue of ladders next to the bus boarding area. The number of ladders grew throughout the two days I was there…I had no idea what they were for until launch day. As it turned out, the ladders were in line for the astronaut walk out. Astronaut walk out is where the crew walks out of the Operation & Checkout (O&C) building, gives a wave to the crowd, and boards the Astrovan for the trip to the launch pad. The entire event is over in less than one minute. The ladders are used by photographers to get a view over the massive crowd looking towards the doorway where the astronauts walk out.

I was perfectly content with my front row view about 10 feet ahead of the Astrovan, away from the doorway. But near the doorway, it was a madhouse with a sea of people and ladders. After about 30 minutes of waiting with anticipation, the crew walked out, stopped in front of the van, waved for about 30 seconds, and hopped aboard the famous Airstream Astrovan. The motorcade was led by an unmarked police cruiser, the Astrovan itself, and followed by a NASA swat team armored vehicle. A security NASA Huey helicopter followed the motorcade.

Ladders waiting in line next to buses.

Crowd waiting for the crew to walkout of the O&C building to the Astrovan.

Helmets come out first.

Followed by the crew.

Right to left: Commander Mark Kelly, Pilot Gregory Johnson, Mission Specialists Michael Fincke, Roberto Vittori, Andrew Feustel, and Greg Chamitoff.

View looking towards the doorway where the crew walked out , and wire service cameras mounted in between pillars.

Mission stickers surround the doorway leading out the O&C building.

While on the bus heading back to the Press Site, I received a text message from a friend also attending the launch saying the launch had been scrubbed and they were detanking. I thought it was a joke. How can that be? I just saw the crew walk out; they are on the Astrovan headed to the pad.On board the bus (I did not see this myself) someone noticed the Astrovan going the opposite direction back to the O&C building. After arriving back at the Press Site, we heard the official word that the launch had been scrubbed due to a hydrazine fuel line heater failure. It was unknown whether they would reattempt launch in 24, 48, or 72 hours. It was all dependent on the resolution of troubleshooting.

President Obama and the First Family had scheduled to come to KSC to watch the launch. Word had it that the President was still coming to tour the facilities despite the launch scrub. Hoping to get a photo of Air Force One landing, we tried to see if we could still make it. But we were told that we missed the sign up and it was not possible to go. We ended up watching Air Force One (C-32A, Boeing 757 variant) arrive from Alabama and land at the Cape Canaveral Skid Strip live on NASA TV. Two Marine One helicopters and two Sea Stallion helicopters ferried dignitaries from the Skid Strip to the Shuttle Landing Facility where they were picked up by motorcade to be taken to the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB). I was disappointed that they didn’t use the helipad next to the Press Site where I had positioned myself. Disgusted (after waiting all that time in the sun), I went back inside the News Center and didn’t bother to wait for the motorcade to come by. A couple hours later, again on NASA TV, we saw President Obama step aboard Air Force One (this time, a C-25A, Boeing 747 variant) and depart the Skid Strip for his next event in Miami. This caught everyone off guard – apparently the President had made an aircraft equipment change there at the Cape.

Presidential entourage flying over Pad 39A.

Presidential movement.

I went back to my hotel thoroughly disappointed – all that planning and setup and then a big let down. I found my travel partner friends (who also came out to watch the launch) enjoying themselves on the beach. I was glad they were able to have a good time despite the disappointment. My friends Dave, Trevor, and Mark made the trek to Florida with me for the first launch attempt. Only I returned for the second attempt.

My friends Dave, Trevor, and Mark made the trek to Florida with me for the first launch attempt. Only I returned for the second attempt. The next morning, Saturday, it was still unknown whether the launch would be Sunday or Monday. Us remote photographers were allowed to go back to the sites to check up on our camera gear. It is known as “bagging”, where photographers bag their gear to protect their camera while waiting for the launch delay (my cameras were already bagged as part of my normal setup).

Remote cameras being bagged due to the launch slip.

Upon arriving at the pipeline, I was happy to see both of my cameras survived the thunderstorm the previous night. There was no water or residual moisture inside the bags. The tripod legs had some dried mud splatter and lenses had water spots. I cleaned off the lenses, checked the battery levels (still good), checked the timer (still had good times) and ensured the trigger still worked. I walked away relieved.On Sunday afternoon, it was announced that the heater problem was caused by an electrical short in the aft load control assembly, a switch box in the shuttle’s aft compartment. The switchbox itself was to be replaced and retested, and new wiring installed to bypass the suspect wiring. This would be an extensive repair. The launch was now delayed one week to at least the following Monday, eight days later. The next morning, I retrieved my remote cameras. I stayed at the Cape to photograph an Atlas V launch on Friday. On that day, I found out STS-134 had been delayed officially to no earlier than May 16, ten days later.

I was able to setup a remote camera for the Atlas launch on the pad, about 500 feet away from the rocket. I had success…I was stoked! This boosted my confidence level that my remote shots were actually going to work for the shuttle!

After the Atlas launch on Saturday (itself delayed one day due to weather), I went home with plans to return for the next shuttle launch attempt.

On to Part 2.

Lots of information in this blog Ben, thanks for sharing. Hopefully, you can arrange it where you can go get the last shuttle launch. If not, you could always come to Dallas and photograph QANTAS. :)

ReplyDelete